Learning Concepts in C++ Part 5: Vector Spaces

link to repository https://github.com/jgsuw/math_concepts_cxx

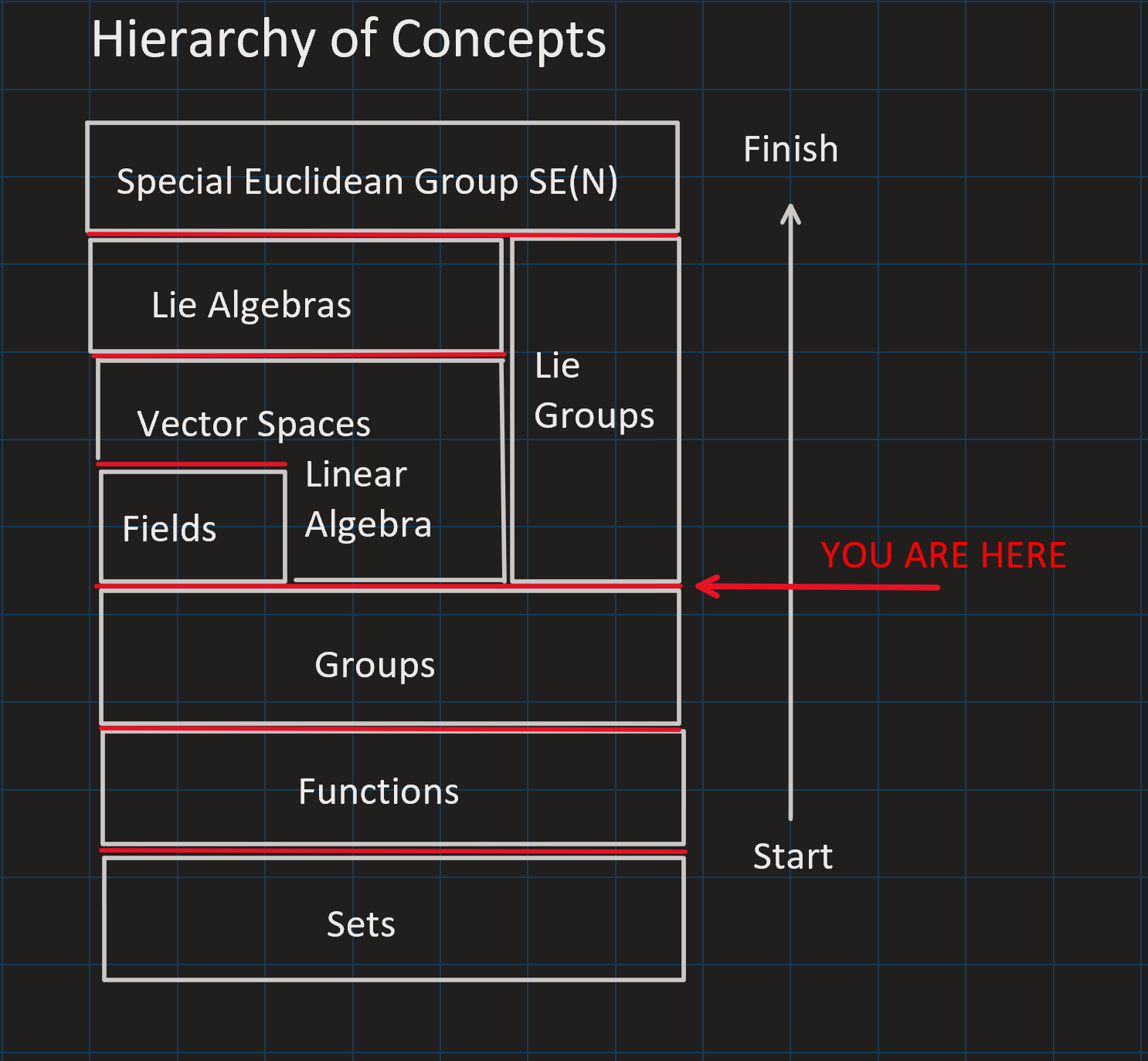

On the path to \(\text{SE}(3)\)

This entry is part 5 of an ongoing series cataloging my experiments with the Concepts and Contraints on templates in C++20. In part 1, I set a goal of creating a template library for the Special Euclidean Group \(\text{SE}(3)\) and its Lie Algebra \(\text{se}(3)\) by building a hierarchy of mathetmatical abstractions using constrained template concepts.

In my last post I implemented a Field concept which built upon a Groups which provides an abstraction for the algebra of rational numbers \(\mathbb{Q}\), reals numbers \(\mathbb{R}\), complex numbers \(\mathbb{C}\) among others. The field concept is an essential requirement for the topic of this post, Vector Spaces.

Vector Space Axioms

Keeping the approach from previous posts, I set out to create a VectorSpace concept which encodes the axioms of a Vector Space as constraints on a template class. When I was an undergraduate student learning Linear Algebra, I was taught a definition of Vector Spaces that used 8 axioms. Fortunately, half of these axioms are already subsumed by the AbelianGroup concept defined in part 3.

A Vector Space over a field \(\mathcal{F}\) is a set \(V\) with operations \((+_V,\cdot)\) called vector addition and scalar multiplication which satisfies

- \((V,+_V)\) is an Abelian Group

- \(\cdot: \mathcal{F} \times V \to V\), \((\alpha, x) \mapsto \alpha x\) satisfies: – \(1\), the identity of multiplication on \(\mathcal{F}\), fixes $\cdot$ to the identity function: \(\forall x \in V : 1\cdot x = x\) – scalar multiplication distributes through \(+_V\), i.e. \(\forall \alpha \in \mathcal{F}, x,y \in V : \alpha \cdot (x +_V y) = \alpha \cdot x +_V \alpha \cdot y\) – scalar multiplication distributes through \(+_\mathcal{F}\) i.e. \(\forall \alpha, \beta \in \mathcal{F}, x \in V : (\alpha +_\mathcal{F} \beta) \cdot x = \alpha \cdot x +_V \beta \cdot x\)

here I have used subscripts on addition to distinguish addition on the field \(+_\mathcal{F}\) with addition on the Vector Space \(+_V\). As we have seen several times before, these axioms involve the universal and existential quantifiers \(\forall, \exists\) which in English say “for all … there exists”. What follows these quantifications are predicates that vary over the set being quantified.

In this way, we may view the second axiom about the identity property of scalar multiplication as

\(\forall x \in V : P(x)\), where \(P(x) \iff 1 \cdot x = x\).

Remark on The Limitations of Concepts

It bears repeating that while the compiler is capable of evaluating \(P(x)\) for any constant expression \(x\) (i.e. where \(x\) refers to a compile time constant), it certainly cannot check the quantified predicate \(\forall x \in V : P(x)\) in general, because this would require enumerating every \(x \in V\) as a compile time constant. To drive this point home, the Lie Algebra \(\text{se}(3)\) is a vector space over the reals, which is an uncoutably infinite set.

Nevertheless, I will proceed in a similar fashion to previous posts, and encode the unqantified predicates of the above axioms into the Vector Space concept. This exercise is not just pedagogical; if done thoughtfully, encoding the unquantified predicates also documents the mathematical equivalent of the concept and provides a way to test the validity of the concept on a set of test data at compile time.

Vector Space Concept Definition

Here I implement a concept VectorSpace which evaluates a template class VecSp that represents a vector space over a field VecSp::F, with vectors belonging to the (point) set VecSp::V, and that has an addition operator VecSp::Add and scalar multiplication operator VecSp::Mul.

template <class VecSp>

concept VectorSpace =

Field<typename VecSp::F> &&

AbelianGroup<typename VecSp::V, typename VecSp::Add> &&

MapsTo<

typename VecSp::Mul,

CartesianProduct<typename VecSp::F::Set, typename VecSp::V>,

typename VecSp::V> &&

requires (VecSp::F::Set::type& a, VecSp::F::Set::type& b, VecSp::V::type& x, VecSp::V::type& y) {

VecSp::Mul::unity_scalar_fixes_identity(x);

VecSp::Mul::distributes_through_vec_add(a,x,y);

VecSp::Mul::distributes_through_scalar_add(a,b,x);

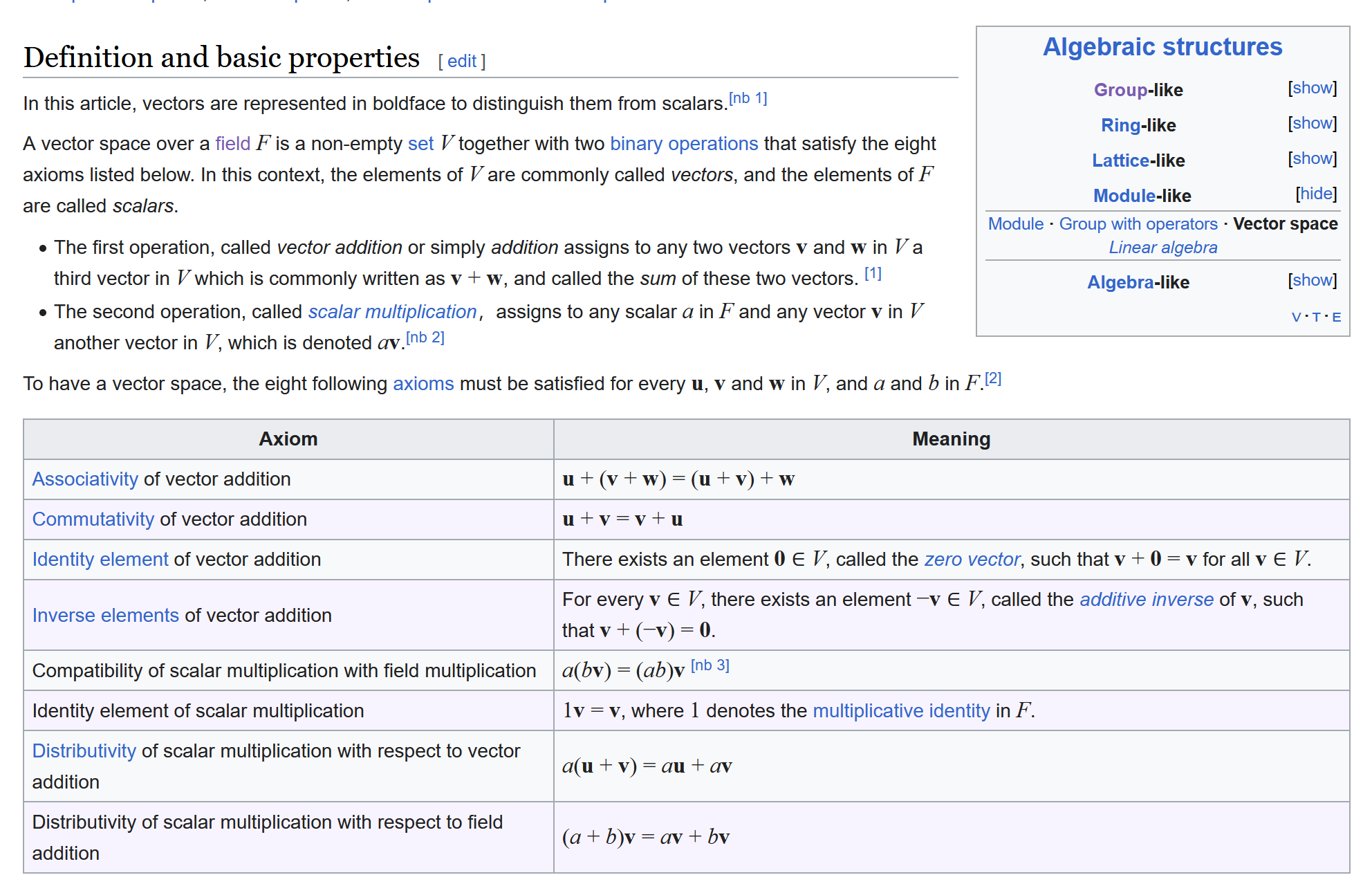

};I have also introduced a new concept, MapsTo<Op,Domain,Target>, which is a convenenience concept that checks that Domain and Target agree with Op::Domain and Op::Target. At this point some might say these concepts are a bit overlong. Myself is not wholly satisfied by the lengthy definition of VectorSpace, despite its reuse of two key concepts Field and AbelianGroup I had previously defined. However, compare the above definition with the Wikipedia definition of vector space:

Comparing the length of the wikipedia definition with the C++ concept definition, I think its fair to say I haven’t done too bad.

Euclidean Space Template

The most common and arguably the canonical vectorspace is (\(n\)-dimensional) Euclidean Space, often simply reffered to as \(\mathbb{R}^n\). For this reason I chose to use \(\mathbb{R}^n\) as an example template that satisfies the VectorSpace concept. For the field \(\mathbb{R}\) I used the RealNumberField template from part 4. For the set of vectors \(V\), I created a template using the Vector template from Eigen:

template <typename T, size_t n>

class Rn {

public:

using type = Eigen::Vector<T,n>;

static bool contains(type& x) { return true; }

};With these templates, the Euclidean Space template is so defined

template <typename T, size_t n>

class EuclideanSpace {

public:

using F = RealNumberField<T>;

using S = F::Set;

using V = Rn<T,n>;

using Vec = V::type;

using Scalar = F::Set::type;

class Add { // Vector addition

public:

using Domain = CartesianProduct<V,V>;

using Target = V;

static inline Vec identity() { return Vec::Zero(); }

static void has_identity(const Vec& x) {

static_assert(apply(identity(), x) == x);

}

static inline Vec inverse(const Vec& x) { return -x; }

static void has_inverse(const Vec& x) {

static_assert(apply(inverse(x),x) == identity());

}

static inline Vec apply(const Vec& x, const Vec& y) { return x + y; }

static inline Vec apply(const Domain::type& x) { return apply(x.first, x.second); }

static void is_commutative(const Vec& x, const Vec& y) {

static_assert(apply(x,y) == apply(y,x));

}

static void is_associative(const Vec& x, const Vec& y, const Vec& z) {

static_assert(apply(x,apply(y,z)) == apply(apply(x,y),z));

}

};

class Mul { // Scalar Multiplication

public:

using Domain = CartesianProduct<S, V>;

using Target = V;

static inline Vec apply(const Scalar& s, const Vec& v) { return s*v; }

static inline Vec apply(const Domain::type& x) { return apply(x.first, x.second); }

static void unity_scalar_fixes_identity(const Vec& x) {

static_assert(apply(F::Mul::identity(), x) == x)

}

static void distributes_through_vec_add(const Scalar& a, const Vec& x, const Vec& y) {

static_assert(apply(a,Add::apply(x,y)) == Add::apply(apply(a,x),apply(a,y)));

}

static void distributes_through_scalar_add(const Scalar& a, const Scalar& b, const Vec& x) {

static_assert(apply(F::Add::apply(a,b), x) == apply(a,x) + apply(b,x));

}

};

};